Uffe Isolotto: Sculpting the Boundaries of the Human and the Inhuman

Uffe Isolotto's intersection of body, technology, and nature.

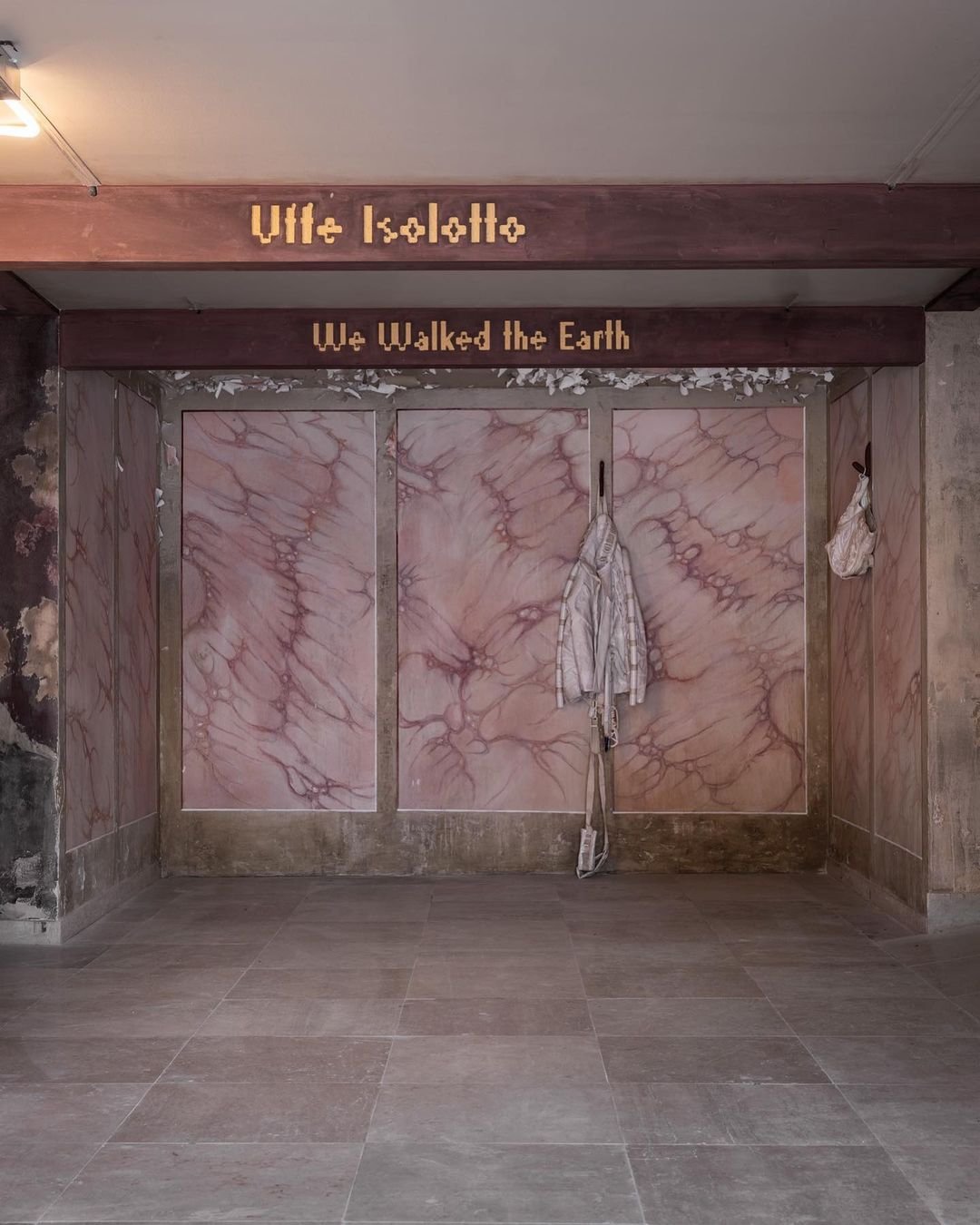

Photo: Courtesy of @uffeisolotto.

In the realm of contemporary art, Uffe stands as a luminary, navigating the intricate intersections of sculpture, film, and animation to craft immersive experiences that challenge conventional boundaries. In this exclusive interview, we delve into the artistic universe of Uffe, exploring the dynamic interplay between his diverse mediums and the ever-evolving landscape of technology and art. We unravel the complexity of his creative journey, from the captivating pieces at the Venice Biennale to the exploration of posthuman states.

Uffe's artistic ethos unfolds as he reflects on his distinctive approach to art, viewing it not merely as a medium but as a tool. His immersive installations serve as a testament to his desire to elicit visceral and real reactions, prompting viewers to question the essence of bodily experience in a world increasingly driven by technology.

Embedded in the creative heartbeat of Copenhagen, Uffe sheds light on the city's influence on his practice, drawing inspiration from its rich history in art institutions, galleries, and furniture design. As the conversation unfolds, Uffe generously shares insights into his collaborative ventures, including the Age of Aquarius platform co-created with his wife, Nanna Starck. There’s a glimpse into the artist's future endeavors, offering a tantalizing preview of upcoming projects that weave together themes of uncertainty, ecology, and existentialism. Join us as we delve into the mind of Uffe, where art transcends traditional confines and beckons us to contemplate the ever-evolving tapestry of our humanity.

Photo: Courtesy of @uffeisolotto.

Karen: Your work encompasses various mediums, from sculptures to film and animation. How do these different forms of artistic expression contribute to your exploration of our changing technological art scene?

Uffe: I've used technology before to create films that could be captured or 3D animation, but I always return to the sculpture approach because it has to have some tangibility. Right now, I'm less into using technology as a way of expressing myself and more as a tool. I can't use it until it makes sense. I'm curious about things like algorithms, but it doesn't make sense to start with the algorithm and then do the work. I have to find a place where it fits in. I use it when it feels right. I do a lot of research on projects that I don't ever realize. You should see my desktop; it's cluttered. I have tabs, windows, and folders, and sometimes you stumble through it, and it makes sense to flow with the ideas, images, and technology. Finally, I connect some dots and go from there. So, it's not like I'm waiting; I'm just having it as an option, like an open tab.

Karen: Your art often challenges traditional notions of the human and the non-human. What role do bodies have in your work? What is their message?

Uffe: I think they're everything because I'm quite aware of the viewer in the work. To make an impact, you have to speak to the body. If you address the body as a sculptural presence or in an immersive installation, you have direct access to people's attention. It's a layered process. In Venice, I wanted to grab people by the guts. So there wasn't any wall text; I just wanted them to be open until they encountered this hyperreal thing in front of them, making them question what it was because there were no answers.

The body is crucial; we often forget we have one. But what does it mean to have bodily experience? It can be emotional because there are a lot of emotions in our bodies, and of course, there are also thoughts behind it. There are layers, and there are themes, quite big aspirations for what these works should convey or give ground to. You need to ground first before you access this very abstract plane.

I started out making small pieces in the corner of a space because of the economy; I was a student and didn't have the money. I decided at one point that I needed to scale up because it became too much about reading and less about experiencing. You read an object, you read a painting, and I want to go beyond that.

Photo: Courtesy of @uffeisolotto.

Karen: As an artist based in Copenhagen, how does the city's creative atmosphere influence your work and collaborations?

Uffe: The city offers a rich tapestry of art institutions, galleries, and a significant history of artist-run spaces. This environment has certainly left its mark on me, especially as I've been part of co-directing a couple of these spaces. Additionally, Copenhagen has a strong tradition in furniture design and architecture, which has recently become more of an interest for me. I've started delving into space and architecture, creating immersive experiences that require an awareness of the architectural context and how visitors engage with the exhibition. This shift in focus has led me towards design. In the Venice project, I collaborated with furniture and fashion designers, working with a diverse team similar to a film set. As the director of the film, I brought it all together, ensuring it was compelling enough. While I'm influenced by these aspects, having never lived elsewhere, I can't directly compare it to other cities. Nonetheless, my creative process has been shaped by various spaces.

Karen: You mentioned that you've never lived in another city; is that because you are well-established in Copenhagen with your family and work?

Uffe: Yes, family is a significant factor, especially with two teenage kids. While I'm venturing to New York this year and LA in February, I don't see myself as a typical Danish artist. My work, being more figurative, expressive, and emotional, doesn't quite fit the traditional mold here. I'm open to exploring other places; Mexico could be one of them. I'm eager to create narratives that resonate in a meaningful way beyond geographical boundaries.

Photo: Courtesy of @uffeisolotto.

Karen: You've mentioned that your work places itself in a posthuman state. Can you explain what this means to you?

Uffe: It's a term we frequently discuss. I like to reflect on our history with technology – whether it's a rug, a stick, or any tools or interfaces connecting us to the world. That's technology, and nature is just us. We're not separate from nature; we are a part of it. This realization has become more pronounced in recent decades. I don't view things as opposites. Being post-human means considering ourselves not the center of the universe. I don't believe we'll ever transcend being human. We're constantly expanding and evolving. Conversations about robotics or AI may seem strange and fearful, but it's essentially a fear of ourselves.

Karen: I notice you don't talk about "your vision" or "your way of thinking"; you speak in the plural. It's a different approach than what artists typically take.

Uffe: Yes, speaking as a contemporary artist involves a constant fluctuation and temporality. I believe it's crucial to address others. It's not about the artist imposing their vision; I don't believe in that. I enjoy gaining additional insights and collaborating with others, not limited to fellow artists.

Karen: You run the exhibition and production platform "Age of Aquarius" with Nanna Starck. How has this collaboration influenced your artistic practice, especially in terms of merging body, technology, and ecology?

Uffe: The Age of Aquarius, which my wife Nanna and I initiated, is located on the top of a public building where we have a garden – a blend of private and public spaces. It's an inviting area because Copenhagen generally maintains a flat skyline. We aim to bring people into the garden to discuss various ecologies – synthetic or biological. We curated shows, invited artists, and worked together since my wife is also an artist. The concept was to merge life and art while exploring the integration of body, technology, and ecology. This idea wasn't as prevalent when we started, but now many spaces delve into it. We embraced the term "Age of Aquarius" from the musical "Hair" to adopt a tongue-in-cheek spiritual yet honest approach. It has influenced me significantly, aligning with the themes from my other works. While the platform may be somewhat hibernating now due to busyness and perhaps reaching its course, it has been an enriching experience.

Karen: How has your participation in TOVES – the Scandinavian artist collective and project space – shaped your artistic journey?

Uffe: It began right out of art school, a mix of friends and unfamiliar faces brought together by another artist's invitation. We initially had more people involved, but it eventually settled with 10 participants due to others having different plans. What I gained from it was an experience of lots of communication, not necessarily consensual, where everyone had a say. We reached some interesting places, and it became one of those factors shaping my artistic course. Simultaneously, I worked as an artist assistant for five years, which introduced me to the gallery world and deepened my understanding of museums. Art school, artist-run spaces, and being an artist assistant provided me with a broader view of the art world than I would have gained without these experiences.

Karen: Having graduated from the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in 2007, how has your artistic style and perspective evolved since then? How have you changed after your participation in the Danish pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2022?

Uffe: I initially started with a background in poetry before entering art school, where I transitioned to visual art but retained a poetic approach. I found that the way I liked to write could be translated into creating artwork, treating the page as a space and words as objects. This led me to working with ready-mades, combining objects with existing meanings, and pushing them into new spaces through extensive research. My practice evolved through various phases, including collaborations with other creatives, from blacksmiths to 3D artists, which allowed me to approach my work from an overall perspective.

For Venice, I collaborated with designers, taxidermists, and others, marking a significant shift. The Biennale participation was an open call from the Danish Arts Foundation, bringing financial support and exposure. This experience changed my practice over the past three and a half years. I enjoy long processes, like creating different versions of one show in various places, although it requires project management skills and navigating human relations. It can be challenging, but it's also rewarding.

Karen: About the Venice Biennale, can you tell us more about the ideas and concepts you explored in the pavilion?

Uffe: The concepts in the pavilion are broad, touching on the future of humanity and depicting emotions and feelings of the present. Created before COVID-19 and recent global events, I aimed to build a world using the concept of world-building from video games, literature, and film. This world explores complex themes such as identity, existentialism, gender, ecology, climate, motherhood, and fatherhood. With the extended exhibition timeline, I had the opportunity to delve into these ideas, creating something complex yet beyond specific themes – an open yet closed world.

Photo: Courtesy of @uffeisolotto.

Karen: In a world of mass production, the motto "do it yourself" can bring a sense of authenticity to art. How do you balance the desire for authenticity with the demands of the art market or audience expectations?

Uffe: I have the luxury of not having a gallery. Throughout my career, I've had many years of not producing for an art market, so it feels like I've always been doing it myself, and that's hard to change. I'm pretty hard-wired when it comes to making what I want.

I'm more cautious about the audience's expectations. When you create something, people expect the next exhibition to be the same. In my case, I rarely repeat myself. I strive to create something beautiful, impactful, something that evokes emotions. When you strike that chord and create something that has this effect on people, you put demands on yourself.

Karen: What’s coming next?

Uffe: I'm still working with the Centaurs. After Venice, I exhibited it in Copenhagen, funded by the Danish state. Recently, I opened an exhibition in Riga, Latvia, showing it in another version, adapting to a slightly different cultural context. The exhibitions are evolving in different iterations, and I would love to take it to different contexts when the opportunity arises. Eventually, I plan to close it off and create a publication to sum it up.

I'm also working on a large-scale installation related to coping with uncertainty and the ecological crisis in the world. Additionally, I want to create some smaller works without the logistical challenges and large production scale.